Imagine for a moment: You can experience the memories of anyone else—not just view the recollections, but think their thoughts and feel their feelings. The only price? Making your memories available to be seen by others. (Anonymously, of course—assuming nobody will use context clues to piece together whose memory they’re seeing.) Would you do it?

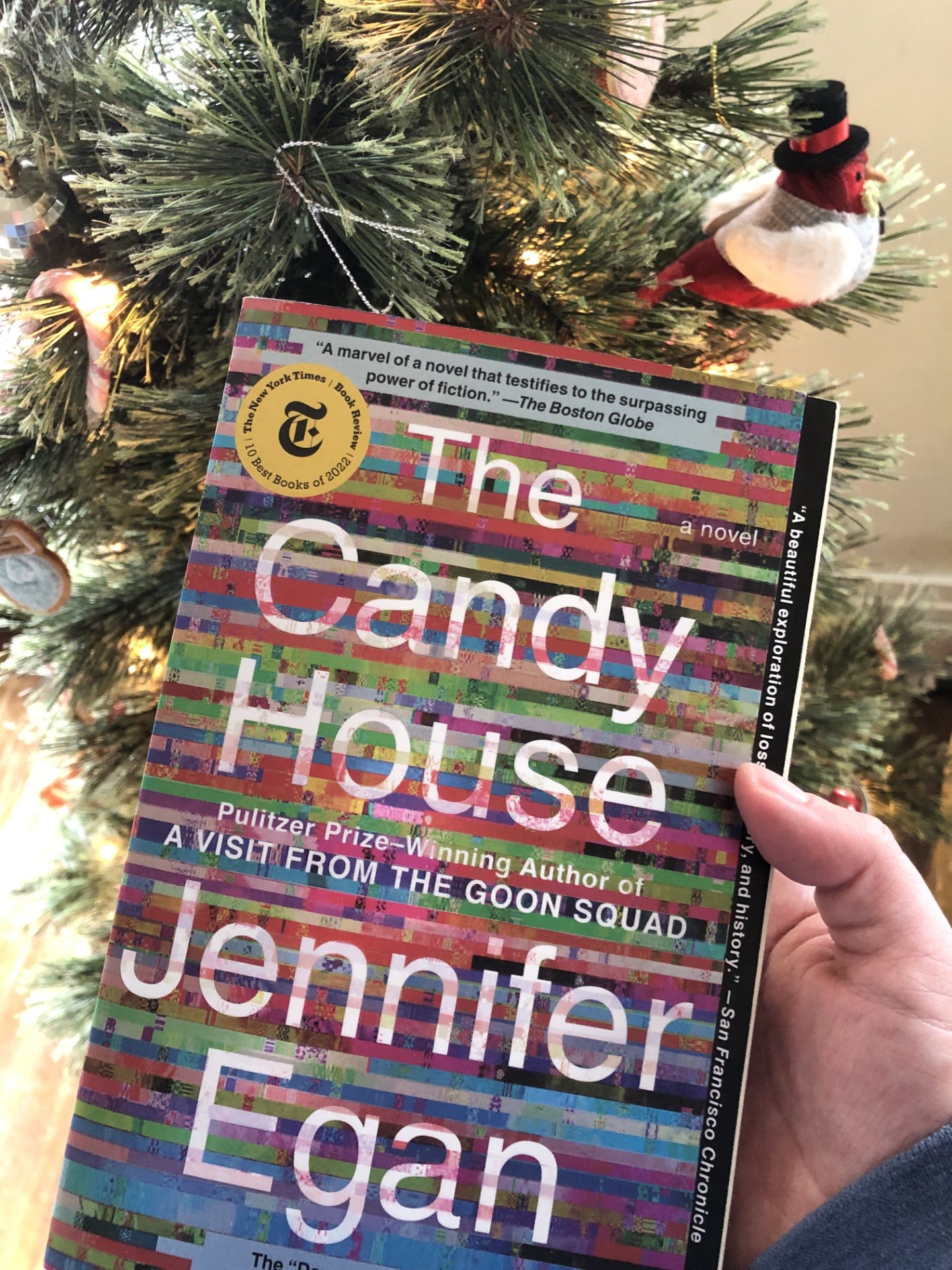

Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House envisions a near-future in which most of the world says, “Yes!” In the next evolution of social media, tech entrepreneur Bix Bouton brings to market Own Your Unconscious, an externalization of one’s memories into a format that can be viewed, experienced, and shared. Bix and his company, Mandala, claim to have brought forth Own Your Unconscious to solve particular problems, which it did:

“[T]ens of thousands of crimes solved; child pornography all but eradicated; Alzheimer’s and dementia sharply reduced by reinfusions of saved healthy consciousness; dying languages preserved and revived; a legion of missing persons found…” (309)

A Collective Consciousness emerges, in which people dump their anonymized memories so that they can view others’ in exchange. Of course, someone seeking out a particular person’s memory can find it if they work hard enough. Anonymity, then, is a loose concept. The only way to keep your memories truly anonymous is to choose never to share them.

Egan’s novel-in-stories focalizes an intersecting cast of characters across decades, piecing together the ways in which their lives fit together. Those individuals make drastically different decisions in response to Own Your Unconscious. Some are all in; others become “eluders,” working to keep their memories private even if it means leaving their identities—and the memories other people have about them—behind. While there are plenty of interesting questions raised about the role of technology in our lives and the motivations for externalizing one’s consciousness to a cube, what I’m interested in (and what I think Egan is interested in, too) is the relationship between history and memory. Throughout the novel, characters are largely interested in the construction of narratives—using multiple people’s memories to more fully understand a particular event, performing a role to get what they want through deceit, making meaning out of things that happen to them. With (almost) everyone’s memories swirling around in a centralized database, the question becomes, what is true?

Charlene is the daughter of Lou Kline, a deceased record producer who left behind a number of exes and children. In “What the Forest Remembers,” she plays the role of mostly omniscient narrator—by experiencing the memories of her father and the people around him on one weekend in June 1965, she reconstructs the story of that weekend in the third person. She strives for accuracy in her telling, representing it as both story and history:

“How can I presume to describe events that occurred in my absence in a forest now charred and exuding an odor like seared meat? How dare I invent across chasms of gender, age, and cultural context? Trust me, I would not dare. Every thought and twinge I record arises from concrete observation, although getting hold of that information is arguably more presumptuous than inventing it would have been” (132)

She does this even if doing so may be painful. Take, for example, a “concrete observation” from her father’s thoughts as he left for the weekend trip: “[Lou] has a guilty awareness of loving Rolph more than Charlie. Is that wrong?” (131).

The weekend in question sees Lou and three friends smoking weed for the first time; on that trip, Lou has the first spark of inspiration that will lead him to build his recording empire—and to leave behind his first wife and their children, Charlene and Rolph. That, of course, is why we care about this particular weekend.

Because, for all Charlene’s insistence that this is concrete observation, not invention, there is one fundamental invention present in the story: context.

What we consider history—what we consider worth observing and retelling—must be significant in some way. Significant not because it happened to someone, but because it impacted someone else. That’s the context which makes meaning out of memory.

Even under the guise of omniscience, Charlene provides us with the necessary context to understand why this moment matters. She reveals herself as the narrator, which orients our attention around Lou—and around his relationship with her. And the combination of mentions of her in other chapters and additional information she provides in this chapter confirms the significance of this moment in Lou’s life: it sets him on a course toward career change and divorce. If we didn’t have this context, we might not care about this chapter, about four men getting stoned, at all. Or we might be more interested in the queer love story bubbling up between two of the other men in the group, or the other people at the sort-of-commune.

Charlene understands this, notes it in an admission of guilt—the guilt of invention: “[M]y problem is the same one had by everyone who gathers information: What to do with it? How to sort and shape and use it? How to keep from drowning in it? Not every story needs to be told” (139).

As the narrator, Charlene has chosen which story needs to be told—which story needs to become history. She has shaped and used information to craft a narrative that, even if factually accurate, is not necessarily true. In this telling, the story is one of a man tasting something he wants more than what he already has and deciding to walk away from a life he built. Would Lou tell the story that way? Or would his be one of enlightenment, the discovery of a passion—producing music—that he stayed committed to for the rest of his life? For Charlene, at least, this is the truest version of the story, regardless of what Lou would tell, because it is formed in the crucible of her context. She may not have invented across “cultural context” to capture the events of the story, but she regardless cast the story in a new context that altered it. Lou’s version of events would be true, too, but it would also be different.

Truth, context, memory—these are things I think about often. Especially in relation to my transition.

When I came out to my family, they seemed to fixate on the meaning-making. My Dad wondered how to talk about me in his retirement speech, what photos to include on a flash drive he gave me as a gift. My Mom wanted to keep old (and not-so-old) pictures on the walls, and at my first Christmas after coming out to her, she hung up the stocking I’ve had since childhood, name unchanged. They both told me to give my sisters time to think about how my transmasculinity shifted their memories from growing up together—particularly, sharing rooms as kids.

Of course, my family hadn’t spent years thinking about my gender before I came out; that context was mine. The least I could give them was time.

But I worried—maybe still do—about the meaning they were making out of my identity. Their context was informed by our shared past, yes, but also by religion and politics and age and personal history in different ways than mine. My impulse was to try to convince them that nothing had changed, that I was still essentially the same person. It didn’t work because it isn’t true. We are all changing from one moment to the next; why wouldn’t I be a different person? They were different, too.

I was applying my new context to old memories, as well. Having aha moments where pieces of my childhood self began to fall into place. It was unreasonable for me to want my family not to do that mental work for themselves. I was Lou; they were Charlene.

Eventually, I made peace with the knowledge that I couldn’t control the meaning my family made out of my coming out. With time, I’ll learn the ways in which the contours of our relationships have changed as a result. There is a significant possibility that our truths will never align, and that those misalignments might hurt. I think there’s something tragic about that, if only the fact that my joy may never outweigh feelings of loss or betrayal or disbelief. No matter how much I wish it, I cannot make my truth about my transition everyone’s truth.

But I can choose to believe my truth as truth: the facts of my life, including my transition, are mine, and the meaning-making other people do regarding my life doesn’t change what is true for me.

“The Mystery of Our Mother” is one of those rare successes of the first-person plural narrator. Lana and Melora are the twin daughters of Lou and Miranda Kline—another of Lou’s exes. Miranda is an anthropologist whose research on human relationships became the basis of Bix Bouton’s social-media algorithms that drove his initial success, long (but not too long) before Own Your Unconscious was conceived. Miranda, for her part, is vehemently opposed to Bix’s use of her work, believing it to have contributed to massive invasions of privacy. The chapter charts the time leading up to Miranda’s seminal work, Patterns of Affinity, being published through the eyes of her daughters—a time that also evolves their relationship with their father.

The title, however, is misleading (intentionally so, I know).

Miranda’s trajectory over the course of the chapter is no mystery. We are told immediately that she didn’t think she would ever want children. Though she loves Lana and Melora deeply, she loves her work more—or, at least, differently. When she is finally provided with the means and opportunity to return to school and to her work, she takes it, even if it means her daughters turning away from her and toward their father. Miranda struggles with her contradictory loves, allowing her daughters to patent and sell her algorithms to “the social media giants whose names we all know”, though “she had no idea what [they] were asking” (126). Miranda spends her career in the public eye “rail[ing] against the invasiveness of data gathering and manipulation [and] insist[ing] on the deeply private nature of human experience” (126), then makes the decision to elude: to abandon her online—and real—identity for the sake of privacy, creating a new life and leaving her past behind.

The real mystery is revealed when, in the final seven paragraphs of the chapter, the narration shifts from plural to singular. “I, Melora, the youngest” (126), is the actual narrator of our story, despite having spoken as a representative of both twins. What Melora really wants to understand is why Lana decided to elude, too: “The two of them are likely together, much as it hurts me to think of this” (127).

What confuses Melora is more than just why Lana would elude when she herself hasn’t. It’s something far more existential:

“I’ve wondered endlessly—obsessively—when and how Lana’s perspective began to diverge from mine after so much shared history. If we’d uploaded our memories to the Collective Consciousness, I could pinpoint the moment exactly. But we both knew better than that.” (127)

The facts of their history are, indeed, shared. And Melora narrates them as such, to the point that readers assume that the plural voice is accurate. Ultimately, though, we learn that Melora has been making that same assumption. She seems unable to reckon with the possibility that Lana’s experience of the facts of their history could be—and evidently is—different from hers.

The question is irresistible: After so much shared history, when and how did our perspectives diverge?

But “shared history” is a fallacy. It assumes that there is only one context within which things happen, that there is no meaning-making to be done because there is only one meaning. Like it or not, that isn’t true. We may have “cultural contexts” in common, but those only serve to inform our personal contexts. Since coming out, my familial relationships have grown increasingly complicated because of this fallacy.

Any time someone we know intimately subverts our expectations, we ask ourselves when, how, and—most importantly—why they changed.

Though I wish it wasn’t the case, our current reality positions coming out as one of the most dramatic subversions of expectations. (What else can we expect from a society built around compulsory heterosexuality and a rigid gender binary?) Because those expectations are at once societal and personal—rooted in and learned from systems of oppression but applied within individual relationships—any subversion evokes an intense emotional response. Shock becomes elation at best and horror at worst. So often, there are feelings of betrayal (why didn’t you tell me sooner?) and embarrassment (how did I never realize?). What a big ol’ mess of emotions!

Or, I guess you could be like my brother, who “called it.” (When we were kids, he once said that if he could have a brother, he would want it to be me.)

When a question is that irresistible, we can’t keep someone from asking it. And it goes both ways. People in my life might wonder when and how my gender identity diverged from their expectations, and I might wonder when and how they became the sort of person who reacts to the idea of queerness the way they did when I came out.

Melora, too, will wonder why Lana eluded with Miranda—if they’re even together, which is only supposition. I suspect what Melora is really wondering is, if Miranda and Lana are together, when and how Lana’s perspective on the twins’ decision to sell Miranda’s work changed. Melora notes of Miranda’s response to that decision:

“She never once spoke our names in public or acknowledged, even to us, that we’d made a tragedy of her career by perverting her theory to bring about the end of private life.

But we grew apart.” (126)

When we reread that last line, we, too, can wonder—who exactly grew apart? Melora believes it was Melora and Lana growing apart from Miranda. Or was it Melora and Lana and Miranda all growing apart? Or, though it pains her to consider it, was it Melora growing apart from Lana and Miranda?

We don’t know.

The beauty of the irresistible question in “The Mystery of Our Mother” is that Egan knows it can’t be answered. Not by Melora, not by the readers. For Melora, it’s unanswerable at least partially because she and Lana refused to upload their consciousnesses to the Collective. Given the fact of the Collective’s existence, Melora seems to decide not to attempt to simply empathize—she could either get the “facts” or assume the question will forever go unanswered. She is comfortable guessing that her sister and mother are together, but is not comfortable guessing why Lana would choose to elude.

In our world, there is no Collective, no guaranteed way to get the facts. Will we, too, choose not to make an active effort toward understanding one another—our whens and hows and whys?

Personally, I will always do my best to choose empathy. I want desperately to understand others, to relate to them, to learn from them, to help them. I think trying to empathize with other people—even if we fall short of truly, fully understanding them—is the first and most important step toward loving better. I don’t think a future of liberation for all is possible if we don’t at least try to understand where everyone is coming from, where they’re at now.

When I think about certain people who have responded negatively to my transition, I think about how they’ve been shaped by their cultural context, where feelings of fear or betrayal or even hatred may be coming from. This is emotional labor I’m often asked to do—I’ve been asked to think about how difficult it might be for some people to process my transition, typically as a way to suggest that I should minimize my actual presentation of queerness to be more palatable in a cisheteropatriarchal environment because it would be easier for them. Understanding the perspectives of people who have hurt me doesn’t make me any less hopeful that they will change. And honestly, I think many (most? all?) of those people are choosing not to empathize with me. If empathy is the first step toward loving better, then those relationships of mine won’t be able to shift until the expression of empathy is mutual.

Maybe that sounds improbable. Maybe even impossible. But I’ve learned to empathize with people even when I don’t fully understand them—and it’s helped me understand them better. So I believe other people can do the same.

“Here was his father’s parting gift: a galaxy of human lives hurtling toward his curiosity. From a distance they faded into uniformity, but they were moving, each propelled by a singular force that was inexhaustible. The collective. He was feeling the collective without any machinery at all. And its stories, infinite and particular, would be his to tell.” (323)

This is an excerpt from an epiphany of Gregory Bouton, Bix’s son, months after Bix’s death, in the book’s penultimate chapter, “Eureka Gold.” And in the final chapter, “Middle Son (Area of Detail),” the narrator asserts, “Only Gregory Bouton’s machine—this one, fiction—lets us roam with absolute freedom through the human collective” (333). So, Gregory is (re)discovering imagination, the ability to tell the “infinite and particular” stories of “a galaxy of human lives.”

I would argue, though, that he is gaining more than the self-invitation to invent stories. “The collective” is real people, not fictional ones. Isn’t Gregory’s great epiphany, then, empathy?

As a writer, I believe that the fictions I create are amalgamations of my own feelings and experiences. The line between “fictional” and “real” has always seemed blurry to me. Even if everything in a story is imagined, the context of that story—be that the context in which it’s situated socioculturally or the personal context of who I was when I wrote it and what I was trying to accomplish by writing it—makes it fundamentally real in some hard-to-explain way.

At the root of imagination, at the root of fiction, at the root of truth, at the root of everything: empathy.

What is true? Bix’s accurate recording of consciousness or Gregory’s invention of it? Melora’s certainty in her beliefs and actions or Lana’s unknowability? Charlene’s stitched-together version of one weekend in her father’s life or Lou’s experience of it?

“But knowing everything is too much like knowing nothing; without a story, it’s all just information.” (333)

All of it is true, or none of it: Egan would likely say there’s no real difference there. The stories we tell—novels, poems, newsletters, memories—may be real or fictional or, most often, something in between. But you know what I think?

I think it’s all true.

If any part of this week’s newsletter feels haphazardly stitched together, forgive me—I wrote it over three weeks and did my best to capture my thoughts on the page as succinctly as possible.

This week (1/21 through 1/28) is a global strike for Gaza. Actions you can take include:

Staying home from work

Staying home from school

Not spending any money

Spending only cash and not using banking institutions

Protesting

Calling your representatives

Engaging in an educational opportunity

Participating in strike-related events in your community

Jo and I made sure to get our groceries for the week on Saturday, and we’ll be keeping an eye on opportunities to get involved in our communities.

Last but not least, today’s Marmalade pic: